About this guide

This guide contains solutions for the first 100 problems from the Project Euler website. Full code, in a form of runnable classes, is available on GitHub: https://github.com/Detharon/ProjectEuler

The code is shared for educational purposes, demonstrating how these problems can be approached using Scala. There are many other sites that discuss Project Euler problems, but here, the purpose it twofold: discuss the problem while emphasizing Scala’s strengths of making efficient code that’s easy to understand.

So, whenever possible, a functional programming style is used, avoiding mutable state and vars. Some solutions intentionally deviate from this approach for performance comparison; these are marked with an ‘M’ suffix in their filenames.

While the non-functional style may yield greater efficiency by reducing object allocations, it often results in less readable and more error-prone code, so it is included primarily for contrast and learning purposes.

How to use this guide

My advice would be to read the solutions only when you’ve already solved the problem. It’s normal to struggle at the beginning. The first solution can be unoptimized and too slow to give the final result, but it’s a good starting point to think what can be improved.

Contributing

Even though it’s an individual work, that’s heavily influenced by my personal style, I’m open for contributions. If you want to add your some extra insights, you’ve found an error or a mistake, please send a pull request or raise an issue in GitHub.

Project status

The project it still in progress, with many problems missing. Some of them are solved but not described yet in this book.

Problem solutions

You can find the code for all the problems in the project repository, in src/main/scala directory.

All examples are runnable, and they only print the solution, along the execution time.

A commonly used code can be found in EulerHelper class, but other than that, the solutions are self-contained.

Multiples of 3 or 5

If we list all the natural numbers below 10 that are multiples of \(3\) or \(5\), we get \(3, 5, 6\) and \(9\). The sum of these multiples is \(23\). Find the sum of all the multiples of \(3\) or \(5\) below \(1000\).

Solution

The only tricky part of this exercise comes from the fact that we cannot simply count the multiplies of \(3\), then calculate the multiplies of \(5\), and add these two numbers up. If we did that, then the numbers that are divisible by both 3 and 5 would be calculated twice.

In this solution, we create three sets of numbers. If a number of divisible by both \(3\) and \(5\), then it’s divisible by \(15\), so we can find those numbers and subtract them from the two other sets.

object Euler001 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int = {

val threes = (3 until 1000 by 3).sum

val fives = (5 until 1000 by 5).sum

val fifteens = (15 until 1000 by 15).sum

threes + fives - fifteens

}

}

The problem can be also solved by checking all the numbers to see if they’re divisible by \(3\) or \(5\). Shorter, nothing gets counted twice, but you may find it harder to read.

(3 until 1000).filter(n => n % 3 == 0 || n % 5 == 0).sum

Even Fibonacci Numbers

Each new term in the Fibonacci sequence is generated by adding the previous two terms. By starting with 1 and 2, the first 10 terms will be: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, …

By considering the terms in the Fibonacci sequence whose values do not exceed four million, find the sum of the even-valued terms.

Solution

The numbers are small enough to calculate it in a matter of milliseconds without any optimisations.

Fibonacci implementation is done with a LazyList to make it infinite. Is this an efficient approach?

Not really, because LazyList memoizes all the elements, but we need just the previous 2.

In this case, due to how easy this task is, let’s keep it as it is.

object Euler002 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int =

fibonacci.filter(_ % 2 == 0).takeWhile(_ < 4_000_000).sum

val fibonacci: LazyList[Int] = 1 #:: fibonacciFunction(1, 2)

private def fibonacciFunction(a: Int, b: Int): LazyList[Int] =

a #:: fibonacciFunction(b, a + b)

}

Largest Prime Factor

The prime factors of 13195 are 5, 7, 13 and 29.

What is the largest prime factor of the number 600851475143?

Solution

Before implementing anything, let’s think how finding the prime factors works. Let’s consider the number from the description, 13195. We can just try all the numbers until we hit a prime, then check if it’s divisible by this prime. Once we found a factor, we can just divide the original number by it.

So, the 13195 turns into 13195 / 5 = 2639.

Then 2639 / 7 = 377.

Then 377 / 13 = 29.

And finally 29 / 29 = 1.

In fact, we could check each result to see if it’s a prime, because if it is, then we know that we’ve found the biggest prime factor and can just return it.

But there are some reasons not to do that as well. Let’s take a look at a complete solution, without that final optimization:

import EulerHelper.naiveIsPrime

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler003 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Long = primeFactors(600851475143L).max

@tailrec

private def primeFactors(n: Long, i: Int = 2, primesFound: List[Int] = List.empty): List[Int] =

if (n == 1) primesFound

else if (n % i == 0 && naiveIsPrime(i)) primeFactors(n / i, i + 1, primesFound :+ i)

else primeFactors(n, i + 1, primesFound)

}

The prime check is done in a naive way, by checking all the numbers. It’s not efficient, and in the process we’re checking multiple numbers over and over again, but it’s still blazing fast. Now, the reason why the final optimization was not done, because it would make the app run much slower: doing the same check on longs rather than integers, made the app run 5 times as long.

extension (n: Int) {

def naiveIsPrime: Boolean = n match {

case n if n < 2 => false

case _ => (2 to Math.sqrt(n.toDouble).toInt).forall(n % _ != 0)

}

}

In the end, it doesn’t make sense to overly optimize such a simple problem. Out solution solves it and is easy to understand, so let’s move on.

Largest Palindrome Product

A palindromic number reads the same both ways. The largest palindrome made from the product of two 2-digit numbers is 9009 = 91 * 99

Find the largest palindrome made from the product of two 3-digit numbers.

Solution

A brute-force solution would also work reasonably well, but we can actually reduce the number of numbers to be checked.

We know that multiplying two 3-digit numbers will give us a 6-digit number at most, so the palindrome we’re looking for has the “abccba” form, or: 100000a + 10000b + 1000c + 100c + 10b + a.

If we add those numbers we get “100001a + 10010b + 1100c”. We can then factor out 11, which means that our palindrome has to be divisible by 11: 11(9091a + 910b + 100c)

One of the numbers then has to be divisible by 11, because it’s a prime number. We can start from 990 instead of 999 and decrease the numbers checked by 11.

As for checking if a string is a palindrome, there are many ways to do that. It can be done iteratively, recursively, or with built-in functions like here. Neither changes the run time, so it doesn’t matter much for this problem.

object Euler004 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int = (for {

a <- 990 to 100 by -11

b <- 999 to 100 by -1

} yield a * b)

.filter(n => isPalindrome(n.toString))

.max

def isPalindrome(s: String): Boolean = s == s.reverse

}

Smallest Multiple

2520 is the smallest number that can be divided by each of the numbers from 1 to 10 without any remainder.

What is the smallest positive number that is evenly divisible by all of the numbers from 1 to 20?

Let’s make it easier

First, let’s try to decrease a bit the number of numbers we’ll need to check. We can analyze the simpler problem for which we already know the answer.

The 2520 is divisible by all numbers from 1 to 10. We know that among those numbers, 2, 3, 5, 7 are primes. So, if the number we’re looking for is divisible by all these prime numbers, then it must be a multiple of (2 × 3 × 5 × 7) = 210.

Solution

We can follow the same logic to find a number that’s evenly divisible by all numbers from 1 to 20.

Prime numbers in this set are: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19. The number we’re looking for, then, must be a multiple of 2 × 3 × 5 × 7 × 11 × 13 × 17 × 19 = 9699690.

Let’s try to find that number!

object Euler005 extends EulerApp {

// 2 * 3 * 5 * 7 * 11 * 13 * 17 * 19 = 9699690

override def execute(): Int = Iterator

.from(9699690, 9699690)

.find { n =>

(2 to 20).forall(k => n % k == 0)

}

.get

}

If we wanted to improve it even further, then we can notice that we don’t need to check again if our numbers are divisible by all these prime numbers. Also, multiplies of these numbers, such as 6 (2 * 3), no need to be checked either.

That’s because every number that’s divisible by both 2 and 3 must be divisible by 6.

We don’t need to make it more complex than necessary. The current solution already runs in 1-2 ms on my machine.

Sum Square Difference

The sum of the squares of the first ten natural numbers is,

\(1^2 + 2^2 + … + 10^2 = 385\)

The square of the sum of the first ten natural numbers is,

\((1 + 2 + … + 10)^2 = 55^2 = 3025\)

Hence the difference between the sum of the squares of the first ten natural numbers and the square of the sum is

\(3025 - 385 = 2640\)

Find the difference between the sum of the squares of the first one hundred natural numbers and the square of the sum.

Solution

It’s a pretty straightforward problem. We can simply write down the problem literally, without any optimizations, and we’re good to go. Scala’s expressiveness makes this task a breeze and the resulting code is easy to understand.

To make it extra concise, let’s also define a “square” extension method.

object Euler006 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int = squareOfSums(100) - sumOfSquares(100)

private def sumOfSquares(n: Int) = (1 to n).map(_.square).sum

private def squareOfSums(n: Int) = (1 to n).sum.square

extension (i: Int) {

def square: Int = i * i

}

}

10 001st Prime

By listing the first six prime numbers: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 13, we can see that the 6th prime is 13.

What is the 10001st prime number?

Solution

We can simply brute-force this problem by using the most naive prime check, since the 10001st prime will be a low number. This solution is pretty fast, even though the algorithm is not very efficient.

As you can see, we don’t even filter out even numbers higher than 2 (or all the multiplies of already found primes), but we’ll need these methods later on. For now, a basic algorithm does pretty well.

import EulerHelper.naiveIsPrime

object Euler007 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = Iterator

.from(2)

.filter(naiveIsPrime)

.drop(10000)

.next()

}

And for the reference, that’s how we check if a number is a prime. A brute-force solution, that ran in 13 ms on my machine, which is pretty good already.

extension (n: Int) {

def naiveIsPrime: Boolean = n match {

case n if n < 2 => false

case _ => (2 to Math.sqrt(n.toDouble).toInt).forall(n % _ != 0)

}

}

Largest Product in a Series

The four adjacent digits in the 1000-digit number that have the greatest product are

\(9 × 9 × 8 × 9 = 5832\)

Find the thirteen adjacent digits in the 1000-digit number that have the greatest product. What is the value of this product?

Solution

The number might look daunting, but for any algorithm it’s small enough that we don’t need to optimize it much. This is the shortest solution (code-wise), but also the least efficient. We split the string into 13-element sliding windows, then calculate the product of the digits in each window.

Once we have the list of products, we simply take the maximum. Easy-peasy. Could you explain why this solution is inefficient and what could significantly improve it, even at the cost of no longer being functional?

object Euler008 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = {

val number = "73167176531330624919225119674426574742355349194934" +

"96983520312774506326239578318016984801869478851843" +

"85861560789112949495459501737958331952853208805511" +

"12540698747158523863050715693290963295227443043557" +

"66896648950445244523161731856403098711121722383113" +

"62229893423380308135336276614282806444486645238749" +

"30358907296290491560440772390713810515859307960866" +

"70172427121883998797908792274921901699720888093776" +

"65727333001053367881220235421809751254540594752243" +

"52584907711670556013604839586446706324415722155397" +

"53697817977846174064955149290862569321978468622482" +

"83972241375657056057490261407972968652414535100474" +

"82166370484403199890008895243450658541227588666881" +

"16427171479924442928230863465674813919123162824586" +

"17866458359124566529476545682848912883142607690042" +

"24219022671055626321111109370544217506941658960408" +

"07198403850962455444362981230987879927244284909188" +

"84580156166097919133875499200524063689912560717606" +

"05886116467109405077541002256983155200055935729725" +

"71636269561882670428252483600823257530420752963450"

number.sliding(13).map(_.map(_.asDigit.toLong).product).max

}

}

Mutable solution

In the earlier approach, the sliding windows were completely independent of one another, which made it immutable, but as I’ve also mentioned – pretty inefficient.

By calculating the product of 13 elements, we were performing 11 redundant multiplications in each neighboring window.

Instead, we can maintain a running product — dividing by the digit that leaves the window and multiplying by the new digit that enters it. The only catch here are the zeroes that break the computation chain.

While this approach is definitely faster, it’s also more error-prone and harder to read. For example, consider the following line:

previous = buffer.remove(0).asDigit

It’s not immediately clear that remove(0) returns the element being removed.

Moreover, if the .asDigit call were omitted, the code would still compile and run,

but it would silently produce an incorrect result. For such a small task, the optimization is not worth

the effort, so treat it merely as a mental exercise.

Special Pythagorean Triplet

A Pythagorean triplet is a set of three natural numbers, a < b < c, for which,

\(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\)

For example \(3^2 + 4^2 = 9 + 16 = 25 = 5^2\).

There exists exactly one Pythagorean triplet for which a + b + c = 1000.

Find the product abc.

Solution

The numbers are low enough for a naive approach, so let’s use it, while keeping the code nice and clean.

We need to check all combinations of a, b, c for which a + b + c = 1000 and find those that form a Pythagorean triplet.

This naive algorithm starts from the highest possible ‘c’, keeps the sum of parameters at 1000, while gradually incrementing ‘b’ and decrementing ‘c’ until this it’s possible. This condition (b == c - 2 || b == c - 1) indicates that the next triangle can’t be created this way, so we need to increase the ‘a’ instead, while resetting the other two parameters: ‘b’ to the lowest possible one, ‘c’ to whatever will give a sum of 1000.

It uses a LazyList which does keeps all the previous elements in memory. That’s not something we need, but it makes the code pretty concise. Let’s also try a mutable approach.

object Euler009 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = {

triangles.dropWhile(!isPythagorean(_)).head.product

}

type Triangle = (Int, Int, Int)

val triangles: LazyList[Triangle] = triangles(1, 2, 997)

private def triangles(a: Int, b: Int, c: Int): LazyList[Triangle] = {

(a, b, c) #:: {

if (b == c - 2 || b == c - 1) triangles(a + 1, a + 2, 997 - (2 * a))

else triangles(a, b + 1, c - 1)

}

}

private def isPythagorean(triangle: Triangle): Boolean = {

val Triangle(a, b, c) = triangle

a * a + b * b == c * c

}

extension (t: Triangle) {

def product: Int = t._1 * t._2 * t._3

}

}

Mutable solution

This time let’s aim for maximum efficiency. Even though the idiomatic solution found the solution pretty fast on my machine, the optimized one is about 10 to 15 times faster, even though they share the same algorithm.

It’s also more concise. It looks rather enigmatic, which is the usual pitfalls for the optimized solutions, but in this case the difference in performance was quite substantial.

object Euler009M extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = {

var a = 1

var b = 2

var c = 997

var found = false

while (!found) {

if (a * a + b * b == c * c) found = true

else {

if (b == c - 1 || b == c - 2) {

a = a + 1

b = a + 1

c = 1000 - b - a

} else {

b = b + 1

c = c - 1

}

}

}

a * b * c

}

}

Summation of Primes

The sum of the primes below \(10\) is \(2 + 3 + 5 + 7 = 17\).

Find the sum of all the primes below two million.

Solution

We could use the brute-force method to check all the numbers up to two million, one by one, to see if they’re primes, exactly how we did that before.

It would eventually finish, because we don’t run out of memory, but we wouldn’t learn anything useful this way.

This is the perfect problem to use the sieve of Eratosthenes. If you’ve never heard about it, then I suggest looking it up, as it will be used in the future problems as well: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sieve_of_Eratosthenes

Unfortunately, the sieve itself doesn’t go along well with immutable data structures because its creation is done iteratively, by small incremental changes. This time I’ll only present a mutable version.

In this solution, we’re filling the sieve, which initially considers all numbers to be primes (true) and marks the multiples of existing primes as non-primes (false). Once we hit next number, we know that if its factors were not found already, then it’s a prime. No need for any another check!

While filling the sieve, we’ll also calculate the primeSum to avoid iterating the array again.

It makes it even more mutable with a global state, but also faster.

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler010M extends EulerApp {

private type Sieve = Array[Boolean]

private val limit = 2_000_000

private val sieve = Array(false, false) ++ Array.fill(limit - 2)(true)

private var primeSum = 0L

override def execute(): Long = {

fillSieve(2)

primeSum

}

@tailrec

private def fillSieve(n: Int): Sieve = {

if (n == limit) sieve

else if (sieve(n)) {

primeSum += n

sieveWithNewPrime(n)

fillSieve(n + 1)

} else fillSieve(n + 1)

}

private def sieveWithNewPrime(newPrime: Int): Unit = {

var nonPrime = newPrime * 2

// We will mark all the multiplies of the new prime number, up to 'limit' as non primes

while (nonPrime < limit) {

sieve(nonPrime) = false

nonPrime = nonPrime + newPrime

}

}

}

We could also cut the numbers of elements stored by twice if we don’t check the even numbers, we know that they are not primes, but that would make the solution more complex. We could also use a more memory-efficient structure, such as BitSet, which requires 1 bit to store 1 number, as compared to array of booleans where we need 1 byte to store a boolean. It would also increase the complexity, since BitSets are a bit more tricky to handle. Could also decrease the performance, but I haven’t checked that.

Largest Product in a Grid

In the \(20 × 20\) grid below, four numbers along a diagonal line have been marked in red.

08 02 22 97 38 15 00 40 00 75 04 05 07 78 52 12 50 77 91 08

49 49 99 40 17 81 18 57 60 87 17 40 98 43 69 48 04 56 62 00

81 49 31 73 55 79 14 29 93 71 40 67 53 88 30 03 49 13 36 65

52 70 95 23 04 60 11 42 69 24 68 56 01 32 56 71 37 02 36 91

22 31 16 71 51 67 63 89 41 92 36 54 22 40 40 28 66 33 13 80

24 47 32 60 99 03 45 02 44 75 33 53 78 36 84 20 35 17 12 50

32 98 81 28 64 23 67 10 26 38 40 67 59 54 70 66 18 38 64 70

67 26 20 68 02 62 12 20 95 63 94 39 63 08 40 91 66 49 94 21

24 55 58 05 66 73 99 26 97 17 78 78 96 83 14 88 34 89 63 72

21 36 23 09 75 00 76 44 20 45 35 14 00 61 33 97 34 31 33 95

78 17 53 28 22 75 31 67 15 94 03 80 04 62 16 14 09 53 56 92

16 39 05 42 96 35 31 47 55 58 88 24 00 17 54 24 36 29 85 57

86 56 00 48 35 71 89 07 05 44 44 37 44 60 21 58 51 54 17 58

19 80 81 68 05 94 47 69 28 73 92 13 86 52 17 77 04 89 55 40

04 52 08 83 97 35 99 16 07 97 57 32 16 26 26 79 33 27 98 66

88 36 68 87 57 62 20 72 03 46 33 67 46 55 12 32 63 93 53 69

04 42 16 73 38 25 39 11 24 94 72 18 08 46 29 32 40 62 76 36

20 69 36 41 72 30 23 88 34 62 99 69 82 67 59 85 74 04 36 16

20 73 35 29 78 31 90 01 74 31 49 71 48 86 81 16 23 57 05 54

01 70 54 71 83 51 54 69 16 92 33 48 61 43 52 01 89 19 67 48

The product of these numbers is \(26 × 63 × 78 × 14 = 1788696\).

What is the greatest product of four adjacent numbers in the same direction (up, down, left, right, or diagonally) in the \(20 × 20\) grid?

Solution

This large blocks of numbers may look daunting, but in reality the number of cases we have to check is pretty small. It’s small enough that we can check all of them and then take the maximum.

First, we’ll load the data line by line and then create a 2d array of integers that represents the problem data set:

def prepareData(): Array[Array[Int]] =

loadFileAsLines().map(_.split(" ").map(_.toInt)).toArray

The loadFileAsLines() is a helper method that does exactly what its name says: it loads the file as a list of strings,

where each string is a line.

Let’s define our search function like that:

private def findLargestProduct(matrix: Array[Array[Int]]): Long = ???

Because of how the data was loaded, matrix(0) would return the first row, and matrix(0)(0) will give us the first

element within the first row.

So, we can iterate over all the elements like that:

for (col <- matrix.indices; row <- matrix(col).indices)

The .indices method is pretty convenient as it returns a range that corresponds to the array length, so we don’t

need to worry about going out of bounds.

If we’re at the element of (0, 0), then naturally we can only check the product in three directions: down, right and diagonally (right, down). If we’re going from left to right, do we ever need to check the left direction?

Not really. Because if we’re checking the right direction at (0, 0), it will be the same as checking the left direction at (0, 3). In both cases we’re multiplying these elements: (0, 0), (0, 1), (0, 2), (0, 3).

Likewise, when checking the diagonals, we can check only those going down. Overall, this gives us four directions to check: “right”, “down”, “right-down”, “left-down”.

Checking each direction is a matter of defining right constraints, so we don’t go out of bounds. Let’s analyze how would that look for the “right” direction.

First, we need to define a condition: col < matrix(row).length - 3. The matrix(row).length returns the length of

the first row. We could as well define a constant of 20, but let’s keep it dynamic as a good practice. With this

check, we’re making sure that the last column we’re checking will be 16, so we can check elements 16, 17, 18, 19.

Our array has 20 elements, but they’re indexed from 0, so the last element has index 19.

Let’s summarize it then. Our check for the “right” direction will look as follows:

var max: Long = 0

if (col < matrix(row).length - 3) {

max = Math.max(max, matrix(row)(col) * matrix(row)(col + 1) * matrix(row)(col + 2) * matrix(row)(col + 3))

}

Now we just need to define the checks for other 3 directions and that’s it, we’ll have our solution.

Here’s the complete solution. It’s a mutable one, but just a little bit. We maintain a mutable, local max that keeps

the maximum product we’ve found so far.

object Euler011M extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Long = findLargestProduct(prepareData())

def prepareData(): Array[Array[Int]] =

loadFileAsLines().map(_.split(" ").map(_.toInt)).toArray

private def findLargestProduct(matrix: Array[Array[Int]]): Long = {

var max: Long = 0

for (col <- matrix.indices; row <- matrix(col).indices) {

if (row < matrix.length - 3) {

max = Math.max(max, matrix(row)(col) * matrix(row + 1)(col) * matrix(row + 2)(col) * matrix(row + 3)(col))

}

if (col < matrix(row).length - 3) {

max = Math.max(max, matrix(row)(col) * matrix(row)(col + 1) * matrix(row)(col + 2) * matrix(row)(col + 3))

}

if ((col < matrix(row).length - 3) && (row > 3)) {

max = Math.max(

max,

matrix(row)(col) * matrix(row - 1)(col + 1) * matrix(row - 2)(col + 2) * matrix(row - 3)(col + 3)

)

}

if ((col < matrix(row).length - 3) && (row < matrix.length - 3)) {

max = Math.max(

max,

matrix(row)(col) * matrix(row + 1)(col + 1) * matrix(row + 2)(col + 2) * matrix(row + 3)(col + 3)

)

}

}

max

}

}

Highly Divisible Triangular Number

The sequence of triangle numbers is generated by adding the natural numbers. So the \(7^{th}\) triangle number would be \(1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 = 28\). The first ten terms would be:

\begin{align} 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 36, 45, 55 \end{align}

Let us list the factors of the first seven triangle numbers:

\begin{align} \mathbf 1 &\colon 1\\ \mathbf 3 &\colon 1,3\\ \mathbf 6 &\colon 1,2,3,6\\ \mathbf{10} &\colon 1,2,5,10\\ \mathbf{15} &\colon 1,3,5,15\\ \mathbf{21} &\colon 1,3,7,21\\ \mathbf{28} &\colon 1,2,4,7,14,28 \end{align}

We can see that \(28\) is the first triangle number to have over five divisors.

What is the value of the first triangle number to have over five hundred divisors?

Solution

Generating the triangle numbers is very easy. The real challenge is to find the number of divisors in an efficient way.

The naive method wouldn’t work. You can try it, but it will take too long to finish, because the number that has 500 divisors will be quite large.

Any number can be represented as a product of prime factors. For example, \(28\) is \(2^2 × 7^1\).

We can get these factors by dividing the 28 by its prime factors:

\begin{align} 28 ÷ 2 = 14\\ 14 ÷ 2 = 7\\ 7 ÷ 7 = 1\\ \end{align}

The next interesting thing is, that if we take increase those factors by one and multiply them with each other, we’ll get a total number of factors: \((2+1)(1+1) = 6\).

We can leverage those facts to quickly find the number of divisors, the only thing we need is a list of primes to use.

Let’s assume that our number will fit as a regular integer, in that case, we can get all primes like that:

private val primes: Seq[Int] =

(2 to Math.sqrt(Integer.MAX_VALUE).toInt)

.filter(EulerHelper.naiveIsPrime)

We could also use a sieve of Eratosthenes here, but let’s keep it simple instead.

Getting next triangle numbers is easy, we can do it with a simple recursive function that keeps the current triangle

number as n and the addend that was used to create it as k. Each iteration we increase k by one and calculate

n from n + k.

@tailrec

private def findTriangleNumber(n: Int = 1, k: Int = 2): Int =

if (divisors(n) > 500) n

else findTriangleNumber(n + k, k + 1)

The missing part is to implement the divisors(n) function that calculates the number of divisors of n.

We’ve already discussed the algorithm, let’s think about the method signature:

@tailrec

private def divisors(

n: Int,

primes: Seq[Int] = primes,

divisorsFound: Map[Int, Int] = Map.empty

): Int

nis the numberprimesis a sequence of primes, initially all of themdivisorsFoundis how we can represent the prime factors. Map key is a prime, and value is a factor.- the return value is the number of divisors

Let’s take a look at the whole solution:

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler012 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = findTriangleNumber()

private val primes: Seq[Int] =

(2 to Math.sqrt(Integer.MAX_VALUE).toInt)

.filter(EulerHelper.naiveIsPrime)

@tailrec

private def findTriangleNumber(n: Int = 1, k: Int = 2): Int =

if (divisors(n) > 500) n

else findTriangleNumber(n + k, k + 1)

@tailrec

private def divisors(

n: Int,

primes: Seq[Int] = primes,

divisorsFound: Map[Int, Int] = Map.empty

): Int = {

val prime = primes.head

if (n % prime == 0) {

val newFactor = divisorsFound.get(prime) match {

case Some(factor) => factor + 1

case None => 1

}

divisors(

n / prime,

primes,

divisorsFound + (prime -> newFactor)

)

} else if (prime > n) divisorsFound.foldLeft(1) { case (accumulator, (_, factor)) =>

accumulator * (factor + 1)

}

else divisors(n, primes.tail, divisorsFound)

}

}

It covers three cases:

if (n % prime == 0)

This condition is met when we’re processing a prime that can divide a number.

It will result in the divisorsFound being updated.

else if (prime > n)

If we hit a prime that’s higher or equal than n, then it’s time to calculate the divisors

based on the divisorsFound map. Keep in mind that n decreases every time we find a new divisor.

In fact, we could also use a (n == 1) condition here.

else divisors(n, primes.tail, divisorsFound)

If previous conditions are both false, then it means that we simply need to check the next prime, because the current one is not a divisor and we’re not finished yet.

Closing notes

The solution is functional, it doesn’t mutate any of the collections it uses, but despite that it’s still pretty fast.

Obviously it could be faster, if, for example, instead of calling the primes.tail every time we want to move to the

next prime number we simply maintained an index of which prime we’re processing.

Likewise, creating a new divisorsFound map after every change will be less efficient than reusing a single map

and mutating it.

Large Sum

Work out the first ten digits of the sum of the following one-hundred-digit numbers.

46376937677490009712648124896970078050417018260538

74324986199524741059474233309513058123726617309629

91942213363574161572522430563301811072406154908250

23067588207539346171171980310421047513778063246676

89261670696623633820136378418383684178734361726757

28112879812849979408065481931592621691275889832738

44274228917432520321923589422876796487670272189318

47451445736001306439091167216856844588711603153276

70386486105843025439939619828917593665686757934951

62176457141856560629502157223196586755079324193331

64906352462741904929101432445813822663347944758178

92575867718337217661963751590579239728245598838407

58203565325359399008402633568948830189458628227828

80181199384826282014278194139940567587151170094390

35398664372827112653829987240784473053190104293586

86515506006295864861532075273371959191420517255829

71693888707715466499115593487603532921714970056938

54370070576826684624621495650076471787294438377604

53282654108756828443191190634694037855217779295145

36123272525000296071075082563815656710885258350721

45876576172410976447339110607218265236877223636045

17423706905851860660448207621209813287860733969412

81142660418086830619328460811191061556940512689692

51934325451728388641918047049293215058642563049483

62467221648435076201727918039944693004732956340691

15732444386908125794514089057706229429197107928209

55037687525678773091862540744969844508330393682126

18336384825330154686196124348767681297534375946515

80386287592878490201521685554828717201219257766954

78182833757993103614740356856449095527097864797581

16726320100436897842553539920931837441497806860984

48403098129077791799088218795327364475675590848030

87086987551392711854517078544161852424320693150332

59959406895756536782107074926966537676326235447210

69793950679652694742597709739166693763042633987085

41052684708299085211399427365734116182760315001271

65378607361501080857009149939512557028198746004375

35829035317434717326932123578154982629742552737307

94953759765105305946966067683156574377167401875275

88902802571733229619176668713819931811048770190271

25267680276078003013678680992525463401061632866526

36270218540497705585629946580636237993140746255962

24074486908231174977792365466257246923322810917141

91430288197103288597806669760892938638285025333403

34413065578016127815921815005561868836468420090470

23053081172816430487623791969842487255036638784583

11487696932154902810424020138335124462181441773470

63783299490636259666498587618221225225512486764533

67720186971698544312419572409913959008952310058822

95548255300263520781532296796249481641953868218774

76085327132285723110424803456124867697064507995236

37774242535411291684276865538926205024910326572967

23701913275725675285653248258265463092207058596522

29798860272258331913126375147341994889534765745501

18495701454879288984856827726077713721403798879715

38298203783031473527721580348144513491373226651381

34829543829199918180278916522431027392251122869539

40957953066405232632538044100059654939159879593635

29746152185502371307642255121183693803580388584903

41698116222072977186158236678424689157993532961922

62467957194401269043877107275048102390895523597457

23189706772547915061505504953922979530901129967519

86188088225875314529584099251203829009407770775672

11306739708304724483816533873502340845647058077308

82959174767140363198008187129011875491310547126581

97623331044818386269515456334926366572897563400500

42846280183517070527831839425882145521227251250327

55121603546981200581762165212827652751691296897789

32238195734329339946437501907836945765883352399886

75506164965184775180738168837861091527357929701337

62177842752192623401942399639168044983993173312731

32924185707147349566916674687634660915035914677504

99518671430235219628894890102423325116913619626622

73267460800591547471830798392868535206946944540724

76841822524674417161514036427982273348055556214818

97142617910342598647204516893989422179826088076852

87783646182799346313767754307809363333018982642090

10848802521674670883215120185883543223812876952786

71329612474782464538636993009049310363619763878039

62184073572399794223406235393808339651327408011116

66627891981488087797941876876144230030984490851411

60661826293682836764744779239180335110989069790714

85786944089552990653640447425576083659976645795096

66024396409905389607120198219976047599490197230297

64913982680032973156037120041377903785566085089252

16730939319872750275468906903707539413042652315011

94809377245048795150954100921645863754710598436791

78639167021187492431995700641917969777599028300699

15368713711936614952811305876380278410754449733078

40789923115535562561142322423255033685442488917353

44889911501440648020369068063960672322193204149535

41503128880339536053299340368006977710650566631954

81234880673210146739058568557934581403627822703280

82616570773948327592232845941706525094512325230608

22918802058777319719839450180888072429661980811197

77158542502016545090413245809786882778948721859617

72107838435069186155435662884062257473692284509516

20849603980134001723930671666823555245252804609722

53503534226472524250874054075591789781264330331690

Solution

That’s a lot of long numbers! Fortunately for us, the standard library in Scala makes this task very easy. Code should be self-explanatory, there isn’t much to add.

object Euler013 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): String =

loadFileAsLines().map(BigInt.apply).sum.toString().take(10)

}

The loadFileAsLines() loads the numbers from a text file, lime by line.

Longest Collatz Sequence

The following iterative sequence is defined for the set of positive integers:

\(n \to n/2\) (\(n\) is even)<\br> \(n \to 3n + 1\) (\(n\) is odd)

Using the rule above and starting with \(13\), we generate the following sequence: \begin{align} 13 \to 40 \to 20 \to 10 \to 5 \to 16 \to 8 \to 4 \to 2 \to 1. \end{align}

It can be seen that this sequence (starting at \(13\) and finishing at \(1\)) contains \(10\) terms. Although it has not been proved yet (Collatz Problem), it is thought that all starting numbers finish at \(1\).

Which starting number, under one million, produces the longest chain?

NOTE: Once the chain starts the terms are allowed to go above one million.

Solution

Let’s make aa brute-force solution and see how it works.

We can add one optimization that cuts the execution time in half. Due to how the sequences are calculated, a collatzLength(2n) is always bigger than collatzLength(n) by 1.

So, we can check only the upper half of the range to get the maximum length of the sequence. Here’s the code.

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler014 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = (500_000 until 1_000_000).maxBy(collatzLength)

private def collatzLength(n: Int): Int = {

@tailrec

def collatzLength(n: Long, currentLength: Int): Int = n match {

case 1 => currentLength + 1

case n if n % 2 == 0 => collatzLength(n / 2, currentLength + 1)

case n => collatzLength(n * 3 + 1, currentLength + 1)

}

collatzLength(n, 0)

}

}

My first though when seeing this problem was to use the dynamic programming. After all, we’ll keep hitting the same sub-sequences (such as 16 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1) many times.

I implemented it using a map while keeping it immutable, but it wasn’t a great idea. The code ran much slower. In fact, even with a mutable map it was around 50% slower than the brute-force one.

Often it’s worth starting out from a basic solution. This way there’s less room for mistake, and we have a baseline result that we can improve further.

Mutable solution

Let’s think for a while how can we improve the brute-force solution.

As I’ve mentioned, some operations are done multiple times. We can memoize them, in an array-based cache for fast lookups. Why array? Because map would be much slowe, and we know its max size.

In fact, we don’t have to cache all the values. You can try it out yourself by limiting the cacheLimit: to 100_000.

It should be slower, but still faster than the brute-force solution.

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler014M extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = (1 until 1_000_000).maxBy(collatzLength)

private val cacheLimit = 1_000_000

private val cache = new Array[Int](cacheLimit)

cache(1) = 1

private def collatzLength(base: Int): Int = {

@tailrec

def compute(n: Long, length: Int): Int = {

if (n < cacheLimit && cache(n.toInt) != 0) {

length + cache(n.toInt)

} else if (n % 2 == 0) {

compute(n / 2, length + 1)

} else {

compute(n * 3 + 1, length + 2)

}

}

val result = compute(base, 0)

if (base < cacheLimit) cache(base) = result

result

}

}

As you see we get rid of the optimization to start from 500_000. That’s because, it turns out, it works slightly slower than starting from the beginning, because our cache has a lot of misses this way, and we don’t backtrace the values to fill it.

We could try to do it, but is it worth increasing the complexity of the solution even further, if it already runs in milliseconds? Sometimes it is, but here, I’ll pass.

Epilogue

If it wasn’t a computational problem, but a business-oriented one, then the base, immutable solution would be the one preferred in almost all the cases, due to how simple and safe it is.

The mutable solution has much more places where errors can be made. For example, the ‘n.toInt’ is only safe because we check right before that n is below a cache limit, which prevents the overflow.

Lattice Paths

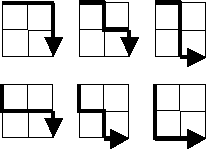

Starting in the top left corner of a \(20 \times 20\) grid, and only being able to move to the right and down, there are exactly \(6\) routes to the bottom right corner.

How many such routes are there through a \(20 \times 20\) grid?

Let’s make it easier

When I saw this problem for the first time my first thought was that I probably can calculate it with a pen and paper.

But since we’re coding in Scala here, let’s try to make an application that will solve it for us.

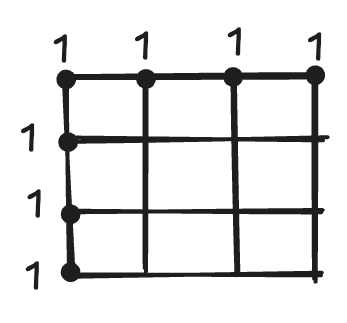

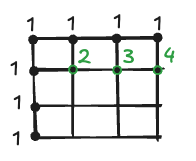

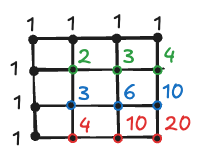

\(20 \times 20\) is a big array, too big to reason about it, while the \(2 \times 2\) is a bit too small. Let’s then draw a \(3 \times 3\) one and mark the edges with dots. How many ways to we have to reach each of these dots? Exactly one way. That was the easiest part.

Now let’s try a second row. If we know how to get to the dot above and to the dot on the left side, then we also know how to go to the dot in question, because from their positions there’s just one way to continue (either left or down).

So, we can fill the second row starting from the left side. First dot will be \(1 + 1 = 2\), second will be \(3 + 1 = 3\), third one will be \(3 + 1 = 4\)

The third row will be no different, let’s continue the process:

And the same goes for the last one. The answer to a question in how many possible ways we can reach the last lattice can be found in the bottom right corner: 20.

Solution

The previous section shown us some properties of the lattice paths. We can now implement the algorithm that we used.

I went for a functional, recursive solution, but a mutable one that’s based on a simple 2-dimensional Array could do as well.

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler015 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Long = countLatticePaths(21, 21)

private def countLatticePaths(length: Int, height: Int): Long = {

val lattice = fillLatticeArray(length, height)

lattice(length - 1)(height - 1)

}

@tailrec

private def fillLatticeArray(length: Int, height: Int, currentResult: Seq[Seq[Long]] = Seq.empty): Seq[Seq[Long]] =

currentResult match {

// First row, we'll fill it with ones

case Nil =>

fillLatticeArray(

length,

height,

Seq(Seq.fill(length)(1L))

)

// All rows filled, time to finish

case other if other.size == height => currentResult

// Filling the next row, but not the first one

case other =>

val nextRowNum = currentResult.size

val previousRow = currentResult(nextRowNum - 1)

fillLatticeArray(

length,

height,

currentResult :+ previousRow.foldLeft(List.empty) { case (result, previousRowNum) =>

result :+ result.lastOption.getOrElse(0L) + previousRowNum

}

)

}

}

It does exactly what we did manually, but on a larger scale. It fills the first row and first column with ones, and then it calculates next elements from left to right, top to bottom. The answer is, as before, in the bottom right corner.

It’s a bit robust, but works pretty fast. What could you improve there?

Tip

Before continuing, think about how can we improve the solution. Can we make it more memory efficient? Can we make it faster? Do we calculate something that’s not needed for the answer?

Mutable solution

It’s not a surprise that making it mutable will make it faster. Just keep in mind that in non-algorithmic tasks the performance gainst might be miniscule, completely outweighed by all the downsides of making it mutable.

So, the first change would be to switch the Seq to an Array. What else can we do?

Previously, we stored all the intermediate results and created a complete, large array with all the values. In fact,

we can calculate the next row knowing the previous row. We don’t need to remember all the other ones. Which means that

there’s no need to maintain a 2-dimensional Array.

My first thought was that we need two arrays, for the current and the previous row. Can we use just one?

In the example with four lattices, the second row contained the following values: \(1, 2, 3, 4\)

If we wanted to calculate the third row by mutating the \(1, 2, 3, 4\) one, then:

- Nothing changes for the first element. It stays as one.

- We add the previous element to the next element, that is, \(1 + 2\), and the second element is \(3\). Our row is now \(1, 3, 3, 4\).

- We do the same for the third element, our row is now \(1, 3, 6, 4\)

- And the last element is calculated with \(6 + 4 = 10\), the row is now equal to \(1, 3, 6, 10\)

- For the next row, we do the same again. \(1\) stays unchanged, the second number if \(4\), another one is \(9\), and so on…

In short, now we only need to keep one row in the memory. Here’s the implementation:

object Euler015M extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Long = countLatticePaths(21, 21)

private def countLatticePaths(length: Int, height: Int): Long = {

val prevRow = Array.fill(length)(1L)

for (_ <- 1 until height) {

for (col <- 1 until length) {

prevRow(col) += prevRow(col - 1)

}

}

prevRow(length - 1)

}

}

Epilogue

Going forward, we could also use this finding to improve the original, immutable solution. But maybe there’s no need to run this iterative computation at all? If you look at those numbers, they seem to be following a certain pattern.

Power Digit Sum

\(2^{15} = 32768\) and the sum of its digits is \(3 + 2 + 7 + 6 + 8 = 26\).

What is the sum of the digits of the number \(2^{1000}\)?

Solution

Due to the rich standard library in Scala, this problem is extremely easy. We can solve it in one line only!

object Euler016 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int = (BigInt(2) ^ 1000).toString().map(_.asDigit).sum

}

It even runs very fast. If we wanted to avoid using BigInt, then it wouldn’t be much harder. We could store the

individual digits in an array and each multiplication would double all the indexes by two. We’d also need to handle

the carrying over.

Still pretty straightforward, not really worth the effort to go through it.

Number Letter Counts

If the numbers \(1\) to \(5\) are written out in words: one, two, three, four, five, then there are \(3 + 3 + 5 + 4 + 4 = 19\) letters used in total.

If all the numbers from \(1\) to \(1000\) (one thousand) inclusive were written out in words, how many letters would be used?

Note: Do not count spaces or hyphens. For example, \(342\) (three hundred and forty-two) contains \(23\) letters and \(115\) (one hundred and fifteen) contains \(20\) letters. The use of “and” when writing out numbers is in compliance with British usage.

Solution

Well, that’s a lot of numbers to cover. Let’s start with something easy, changing one-digit numbers to strings:

private def writeDigit(i: Int): String = i match {

case 0 => "zero"

case 1 => "one"

case 2 => "two"

case 3 => "three"

case 4 => "four"

case 5 => "five"

case 6 => "six"

case 7 => "seven"

case 8 => "eight"

case 9 => "nine"

case _ => throw IllegalArgumentException(s"Received unexpected input: $i")

}

Plenty of code, but it’s very straightforward. We could make it more concise by using an Array, but I like this very

explicit pattern match. What’s next? We can write numbers from 10 to 19:

private def writeTenToNineteen(i: Int): String = i match {

case 10 => "ten"

case 11 => "eleven"

case 12 => "twelve"

case 13 => "thirteen"

case 14 => "fourteen"

case 15 => "fifteen"

case 16 => "sixteen"

case 17 => "seventeen"

case 18 => "eighteen"

case 19 => "nineteen"

case _ => throw IllegalArgumentException(s"Received unexpected input: $i")

}

There’s not much to simplify there yet, because too many words are irregular. 17 is regular, it consists of “seven” + “teen”, so it might seem appealing to pick the last digit to form a prefix, and add “teen” as a suffix, but due to the fact that it’s not very regular, we’d end up with such oddities as 11 represented as “oneteen” :)

Higher numbers, fortunately, are much more regular. For all the numbers between 20 and 99, we can separate the last

digit from those numbers, convert it to a string using the previously defined writeDigit function, and append it

to a string representation of the two-digit number like 20 or 30. Finally, we can reuse some of our previous functions.

If the number is divisible by 10, then we don’t need the output of writeDigit, or we’ll end up with numbers like

20 being written out as “twenty-zero”.

private def writeTens(i: Int): String = {

val remainder = i % 10

val maybeRemainder = if (remainder != 0) Some(writeInt(remainder)) else None

val tens = i - remainder match {

case 20 => "twenty"

case 30 => "thirty"

case 40 => "forty"

case 50 => "fifty"

case 60 => "sixty"

case 70 => "seventy"

case 80 => "eighty"

case 90 => "ninety"

case _ => throw IllegalArgumentException(s"Received unexpected input: $i")

}

maybeRemainder match {

case Some(digits) => s"$tens-$digits"

case None => tens

}

}

What’s writeInt in the code above? It’s a function that writes any int. That’s where we put the guards not to pass

the int into a function that wouldn’t be able to process it. Right now it looks like that:

private def writeInt(i: Int): String = i match {

case i if i >= 0 && i < 10 => writeDigit(i)

case i if i >= 10 && i < 20 => writeTenToNineteen(i)

case i if i >= 20 && i < 100 => writeTens(i)

}

The last part are the hundreds. They’re the most regular, we’ll be able to reuse almost everything we’ve written so far. A number like 123 consists of:

- Written digit (1), using the

writeDigitfunction - “hundred” word

- Written last two digits, using the

writeIntfunction, since we don’t know if we should usewriteDigit,writeTenToNineteenorwriteTens

And here’s the code for hundreds:

private def writeHundreds(i: Int): String = {

val remainder = i % 100

val maybeRemainder = if (remainder != 0) Some(writeInt(remainder)) else None

val hundred = s"${writeDigit((i - remainder) / 100)} hundred"

maybeRemainder match {

case Some(tens) => s"$hundred and $tens"

case None => hundred

}

}

We also need to handle 1000 as “one thousand” and we’re almost done. Here’s the complete solution that convers numbers to strings and counts the letters:

object Euler017 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = (1 to 1000)

.map(writeInt)

.map(_.count(_.isLetter))

.sum

private def writeInt(i: Int): String = i match {

case i if i >= 0 && i < 10 => writeDigit(i)

case i if i >= 10 && i < 20 => writeTenToNineteen(i)

case i if i >= 20 && i < 100 => writeTens(i)

case i if i >= 100 && i < 1000 => writeHundreds(i)

case 1000 => "one thousand"

}

private def writeDigit(i: Int): String = i match {

case 0 => "zero"

case 1 => "one"

case 2 => "two"

case 3 => "three"

case 4 => "four"

case 5 => "five"

case 6 => "six"

case 7 => "seven"

case 8 => "eight"

case 9 => "nine"

case _ => throw IllegalArgumentException(s"Received unexpected input: $i")

}

private def writeTenToNineteen(i: Int): String = i match {

case 10 => "ten"

case 11 => "eleven"

case 12 => "twelve"

case 13 => "thirteen"

case 14 => "fourteen"

case 15 => "fifteen"

case 16 => "sixteen"

case 17 => "seventeen"

case 18 => "eighteen"

case 19 => "nineteen"

case _ => throw IllegalArgumentException(s"Received unexpected input: $i")

}

private def writeTens(i: Int): String = {

val remainder = i % 10

val maybeRemainder = if (remainder != 0) Some(writeInt(remainder)) else None

val tens = i - remainder match {

case 20 => "twenty"

case 30 => "thirty"

case 40 => "forty"

case 50 => "fifty"

case 60 => "sixty"

case 70 => "seventy"

case 80 => "eighty"

case 90 => "ninety"

case _ => throw IllegalArgumentException(s"Received unexpected input: $i")

}

maybeRemainder match {

case Some(digits) => s"$tens-$digits"

case None => tens

}

}

private def writeHundreds(i: Int): String = {

val remainder = i % 100

val maybeRemainder = if (remainder != 0) Some(writeInt(remainder)) else None

val hundred = s"${writeDigit((i - remainder) / 100)} hundred"

maybeRemainder match {

case Some(tens) => s"$hundred and $tens"

case None => hundred

}

}

}

Epilogue

Was it necessary to convert everything to a string? Not at all. We were asked to count the letters only, so if we wanted to be more efficient, the pattern matching could look like that:

case 8 => 5

There are \(5\) letters in the word “eight”. There’s one problem with that approach. Debugging it would be a nightmare. It would be not reusable for anything. The program runs fast already, after all.

There’s one improvement that we could make, though. Those cases aren’t good:

case _ => throw IllegalArgumentException(s"Received unexpected input: $i")

Due to them, our functions aren’t pure. They have a very nasty side effect. Even though they all accept Int parameter,

they can only operate on a subset of numbers. That’s a risky, error-prone design. A much better solution would use

refined types. For example, a separate Digit type that could be only created from numbers 0 to 9. Such types can be

also checked by compiler, so a Digit(10) throws a compilation error rather than a runtime exception.

Maximum Path Sum I

By starting at the top of the triangle below and moving to adjacent numbers on the row below, the maximum total from top to bottom is \(23\).

3

7 4

2 4 6

8 5 9 3

That is, \(3 + 7 + 4 + 9 = 23\).

Find the maximum total from top to bottom of the triangle below:

75

95 64

17 47 82

18 35 87 10

20 04 82 47 65

19 01 23 75 03 34

88 02 77 73 07 63 67

99 65 04 28 06 16 70 92

41 41 26 56 83 40 80 70 33

41 48 72 33 47 32 37 16 94 29

53 71 44 65 25 43 91 52 97 51 14

70 11 33 28 77 73 17 78 39 68 17 57

91 71 52 38 17 14 91 43 58 50 27 29 48

63 66 04 68 89 53 67 30 73 16 69 87 40 31

04 62 98 27 23 09 70 98 73 93 38 53 60 04 23

NOTE: As there are only \(16384\) routes, it is possible to solve this problem by trying every route. However, Problem 67, is the same challenge with a triangle containing one-hundred rows; it cannot be solved by brute force, and requires a clever method! ;o)

Let’s make it easier

We could indeed try to brute-force it, but I did not come up with any elegant brute-force in terms of implementation, so I’ve decided to instead think about solving this problem the ‘intended way’. As usual, let’s think about a nice algorithm that will save us from the necessity of checking all these possibilities. The small triangle will be perfect to plan it.

3

7 4

2 4 6

8 5 9 3

Instead of plotting a route from the top, we could try to do it from the bottom. Can we do something with the last row? Not really. We can’t take the maximum since we don’t know what’s ahead of us, exactly as if we started from the top.

Moving to the row before last, that is, \(2 4 6\), we notice that each of those numbers have exactly two children-numbers. For \(2\), that will be \(8\) and \(5\), for 4, it is \(5\) and \(9\), and so on. If our question was to find the best path for those small sub-problems, with 3-number triangles, then naturally we’d simply pick the bigger children. We can then add it to the parent. That’s how the triangle now looks like:

3

7 4

10 13 15

We can do the same folding to the next row. Just need to pick the “bigger” children. Eventually we’ll end up with that:

3

20 19

And then we fold it once again, leaving us with a single value: \(23\). That’s the maximum path sum.

Solution

For a big triangle, the algorithm remains exactly the same. A natural way to implement it is to mutate the arrays that represent the subsequent rows.

object Euler018M extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int = {

val dataArray: Array[Array[Int]] = prepareData()

var rowIndex = dataArray.length - 2

while (rowIndex >= 0) {

dataArray(rowIndex).zipWithIndex.foreach { case (value, columnIndex) =>

val childrenRow = dataArray(rowIndex + 1)

val maxChildValue = Math.max(childrenRow(columnIndex), childrenRow(columnIndex + 1))

dataArray(rowIndex)(columnIndex) = dataArray(rowIndex)(columnIndex) + maxChildValue

}

rowIndex -= 1

}

dataArray.head.head

}

private def prepareData(): Array[Array[Int]] =

loadFileAsLines().toArray.map(_.split(" ").map(_.toInt).toArray)

}

Very straightforward to implement, as it closely follows what we did on paper with the small triangle, but

unfortunately it mutates both the dataArray and the rowIndex.

For an immutable solution, we need to fold our triangle from the bottom. We can represent it as a

List[List[Int]] and reverse it so we start from the end.

val reversedData = prepareData().reverse

reversedData.tail.foldLeft(reversedData.head) { case (previousRow, currentRow) => ... }

This part starts from the second row (.tail), while the first one goes into the accumulator. Since we always have two

rows available, all we need to do is pick the bigger child and build the next accumulator, which will be our

new previousRow. Here’s the complete solution:

object Euler018 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int = {

val reversedData = prepareData().reverse

reversedData.tail

.foldLeft(reversedData.head) { case (previousRow, currentRow) =>

currentRow.zipWithIndex.map { case (element, index) =>

element + Math.max(previousRow(index), previousRow(index + 1))

}

}

.head

}

private def prepareData(): List[List[Int]] =

loadFileAsLines().map(_.split(" ").map(_.toInt).toList)

}

That’s it! Very concise, fully functional and with a similar run time.

Counting Sundays

You are given the following information, but you may prefer to do some research for yourself.

- 1 Jan 1900 was a Monday.

- Thirty days has September,

April, June and November.

All the rest have thirty-one,

Saving February alone,

Which has twenty-eight, rain or shine.

And on leap years, twenty-nine. - A leap year occurs on any year evenly divisible by 4, but not on a century unless it is divisible by 400. How many Sundays fell on the first of the month during the twentieth century (1 Jan 1901 to 31 Dec 2000)?

How many Sundays fell on the first of the month during the twentieth century (1 Jan 1901 to 31 Dec 2000)?

Solution

I’m afraid there’s no clever way to solve this without writing plenty of code. On the other hand, this problem is pretty straightforward; all we need is some domain modelling. Let’s do it then.

We can start by encoding some simple facts about the calendar. We need to know how many days are in a given month, as well as if the year is leap or not. Let’s also add two helper functions to let us quickly check the century:

private type Year = Int

private def daysPerMonth(year: Year): Array[Int] = Array(

31, // January

if (isLeapYear(year)) 29 else 28, // February

31, // March

30, // April

31, // May

30, // June

31, // July

31, // August

30, // September

31, // October

30, // November

31 // December

)

private def isLeapYear(year: Year): Boolean =

(year % 4 == 0) && (year % 100 != 0 || year % 400 == 0)

def isInTwentiethCentury: Boolean = year >= 1901 && year <= 2000

def isInTwentyFirstCentury: Boolean = year >= 2001

Having those facts laid out, we can try constructing a crude model of a calendar:

case class Calendar(

dayNumber: Int,

dayOfWeekNumber: Int,

monthNumber: Int,

year: Year

)

In this case:

dayNumberrepresents a number of a day in a month, as in June 10dayOfWeekNumberis an internal counter for a day of the week, 0 being Monday and 6 SundaymonthNumberis a number of the month, 0 being Januaryyearis a year type that we’ve defined before

Our calendar needs a way to progress the day while keeping the state of other variables consistent.

It’s not difficult since we have some data to use. Once the dayOfWeekNumber reaches 7 we go back to 0.

Every time we reach a day that’s higher than the daysPerMonth(year)(monthNumber), we either progress the month

or a whole year if we’re at the last month (11 on our case, since we count from 0).

If neither of these checks is met, we simply progress the day.

def nextDay(): Calendar = {

val newDay = dayNumber + 1

val newDayOfWeek = if (dayOfWeekNumber + 1 == 7) 0 else dayOfWeekNumber + 1

if (newDay > daysPerMonth(year)(monthNumber)) {

if (monthNumber == 11) Calendar(1, newDayOfWeek, 0, year + 1)

else Calendar(1, newDayOfWeek, monthNumber + 1, year)

} else Calendar(newDay, newDayOfWeek, monthNumber, year)

}

val dayOfWeek: DayOfWeek = daysOfWeek(dayOfWeekNumber)

val isSunday: Boolean = dayOfWeekNumber == 6

And that’s all we need to calculate it. The condition that we’ll be checking is pretty simple:

if (calendar.isSunday && calendar.dayNumber == 1)

If it’s met, then we’ve found the Sunday we’re looking for. If not, we progress the calendar further, until

(calendar.isInTwentyFirstCentury) – that’s the termination condition.

Here’s the whole code:

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler019 extends EulerApp {

private type DayOfWeek = String

private type Year = Int

override def execute(): Any = {

@tailrec

def sundaysInTwentyCentury(calendar: Calendar, sundays: Int): Int = {

if (calendar.isInTwentyFirstCentury) sundays

else if (calendar.isInTwentiethCentury) {

val newSundays =

if (calendar.isSunday && calendar.dayNumber == 1) sundays + 1 else sundays

sundaysInTwentyCentury(calendar.nextDay(), newSundays)

} else sundaysInTwentyCentury(calendar.nextDay(), sundays)

}

sundaysInTwentyCentury(Calendar.StartDate, 0)

}

case class Calendar(

dayNumber: Int,

dayOfWeekNumber: Int,

monthNumber: Int,

year: Year

) {

private def daysPerMonth(year: Year): Array[Int] = Array(

31, // January

if (isLeapYear(year)) 29 else 28, // February

31, // March

30, // April

31, // May

30, // June

31, // July

31, // August

30, // September

31, // October

30, // November

31 // December

)

private def isLeapYear(year: Year): Boolean =

(year % 4 == 0) && (year % 100 != 0 || year % 400 == 0)

def nextDay(): Calendar = {

val newDay = dayNumber + 1

val newDayOfWeek = if (dayOfWeekNumber + 1 == 7) 0 else dayOfWeekNumber + 1

if (newDay > daysPerMonth(year)(monthNumber)) {

if (monthNumber == 11) Calendar(1, newDayOfWeek, 0, year + 1)

else Calendar(1, newDayOfWeek, monthNumber + 1, year)

} else Calendar(newDay, newDayOfWeek, monthNumber, year)

}

val isSunday: Boolean = dayOfWeekNumber == 6

def isInTwentiethCentury: Boolean = year >= 1901 && year <= 2000

def isInTwentyFirstCentury: Boolean = year >= 2001

}

object Calendar {

val StartDate: Calendar = Calendar(dayNumber = 1, dayOfWeekNumber = 0, monthNumber = 0, year = 1900)

}

}

Mutable solution

While reading the previous solution you might be thinking… why don’t we just use the standard library? Indeed, we can!

In fact, this problem is completely trivialized once we do so. We can simply encode the start date and the end date,

the condition is easily expressed with API for java.time.LocalDate.

import java.time.{DayOfWeek, LocalDate}

object Euler019M extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Int = {

val endDate = LocalDate.of(2000, 12, 31)

var currentDate = LocalDate.of(1901, 1, 1)

var sundays = 0

while (currentDate.isBefore(endDate)) {

if (currentDate.getDayOfMonth == 1 && currentDate.getDayOfWeek == DayOfWeek.SUNDAY) sundays += 1

currentDate = currentDate.plusDays(1)

}

sundays

}

}

Easier, cleaner, better. But in this case, most of the information present in the problem description is not used. We don’t need to check if the year is leap or how many days are in a month. In any project using the standard library would be obviously the way to go, but since we’re just practicing, it makes sense to try to attempt doing it ourselves.

Factorial Digit Sum

\(n!\) means \(n \times (n - 1) \times … \times 3 \times 2 \times 1\).

For example, \(10! = 10\times 9 \times … \times 3 \times 2 \times 1 = 3628800\), and the sum of the digits in the number \(10!\) is \(3 + 6 + 2 + 8 + 8 + 0 + 0 = 27\).

Find the sum of the digits in the number \(100!\).

Solution

Thanks to Scala’s extensive standard library, we can represent the factorial in question as a regular

BigInt. It even has a convenient .factorial method.

Once we have the result of \(100!\), we can recursively read it, digit by digit, using the modulo division.

import EulerHelper.*

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Euler020 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = {

sumDigits(BigInt(100).factorial)

}

@tailrec

private def sumDigits(n: BigInt, result: BigInt = 0): BigInt =

if (n == 0) result

else sumDigits(n / 10, result + n % 10)

}

Amicable Numbers

Let \(d(n)\) be defined as the sum of proper divisors of \(n\) (numbers less than \(n\) which divide evenly into \(n\). If \(d(a) = b\) and \(d(b) = a\), where \(a \neq b\), then \(a\) and \(b\) are an amicable pair and each of \(a\) and \(b\) are called amicable numbers.

For example, the proper divisors of \(220\) are \(1,2,4,5,10,11,20,22,44,55\) and \(110\); therefore \(d(220) = 284\). The proper divisors of \(284\) are \(1,2,4,71\) and \(142\); so \(d(284) = 220\).

Evaluate the sum of all the amicable numbers under \(10000\).

Let’s make it easier

First thing to crack is how to calculate the divisors efficiently. Should we use prime factors? Perhaps, but as a rule of thumb I always start with a simpler approach and move on to a more advanced one if the simple one is not good enough.

If we wanted to find all the divisors of 220, how many numbers do we need to check? We can check from \(2\) to \(110 (220 / 2))), but there’s a better way. Logically, if \(220\) is divisible by \(2\) and we get 110 as a result, then it must be divisible by \(110\) as well. That’s a strong hint that we don’t need to check all the numbers.

How many do we need to check? \(220\) isn’t a great example, so, let’s switch to \(100\), this will be more intuitive. We know that it’s divisible by \(2\), the result of the division is \(50\). We have our first two divisors. Next divisor is \(4\), the result is \(25\). Now we have four divisors: \(2, 4, 25, 50).

Next divisor is \(5\) and \(20\), because \(100 ÷ 5 = 20\). Another one is \(10\). Now that’s a pretty interesting coincidence, that \(100 ÷ 10\) is also \(10\). We no longer have two numbers, just one. Something to keep in mind when designing the algorithm.

Do we need to check further? Let’s pretend that 100 is divisible by \(11\). Obviously it isn’t, but let’s just pretend for a while! In order to get the second number we’d divide \(100\) by \(11\) and it would be a number smaller than \(10\). Which means that it’s a number that we should’ve already found before. The conclusion is, then, that we don’t need to check anything past \(10\).

\(10\) is a square root of \(100\). As long as we keep adding two divisors at once, there’s no need to go past the square root.

Solution

Let’s try to write a function that calculates the divisors based on our previous findings. We also need to keep in mind that every number is divisible by one, so we can start the iteration from \(2\).

private def divisors(n: Int): Seq[Int] = 1 +: (2 to Math.sqrt(n).toInt).flatMap {

case i if n % i == 0 => if (i != n / i) List(i, n / i) else List(i)

case _ => List()

}

The code above does exactly what was described before. If i is a divisor, n % i == 0, then we’ve found two of them,

the: List(i, n / i).

We’re not very close to the complete solution. All we have to do left is to calculate the sum of divisors of numbers under \(10000\), then use that information to find the amicable numbers.

object Euler021 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = {

val divisorSums = (0 to 10000).map(n => divisors(n).sum)

divisorSums.zipWithIndex.collect {

case (sum, index) if sum < 10000 && sum != index && index == divisorSums(sum) =>

index

}.sum

}

private def divisors(n: Int): Seq[Int] = 1 +: (2 to Math.sqrt(n).toInt).flatMap {

case i if n % i == 0 => if (i != n / i) List(i, n / i) else List(i)

case _ => List()

}

}

In my solution, I’m storing the sum of divisors in a Seq, where Seq(1) represents the sum of divisors of 1.

If you think about the signature of divisors(n: Int): Seq[Int], we don’t need to return the Seq[Int] at all here.

We’re interested in the sum, so Int is enough. But with sums alone, debugging would get much more difficult if you

made a mistake in calculating the divisors. It’s up to you though.

In the end, the current solution is pretty fast, so we can stop here and keep it as it is.

Names Scores

Using names.txt, a 46K text file containing over five-thousand first names, begin by sorting it into alphabetical order. Then working out the alphabetical value for each name, multiply this value by its alphabetical position in the list to obtain a name score.

For example, when the list is sorted into alphabetical order, COLIN, which is worth \(3 + 15 + 12 + 9 + 14 = 53\), is the \(938th\) name in the list. So, COLIN would obtain a score of \(938 \times 53 = 49714\).

What is the total of all the name scores in the file?

Solution

It’s a rather easy problem due to a small dataset. No need to use any tricks to solve it.

When processing the names we need to remove the quotation marks that appear as the first and the last character:

name => name.slice(1, name.length - 1)

Here’s the complete solution:

object Euler022 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any =

loadFileAsLines()

.flatMap(_.split(","))

.view

.map(name => name.slice(1, name.length - 1))

.sorted

.zipWithIndex

.map { case (name, index) =>

name.map(c => (c - 'A') + 1).sum * (index + 1)

}

.sum

}

The score calculating part might look a bit enigmatic, so I’ll give a couple words of explanation:

.zipWithIndex

.map { case (name, index) =>

name.map(c => (c - 'A') + 1).sum * (index + 1)

}

The c here is a character, like A, and if we remove A from it then we get 0. So we need to add 1 to it, since A

is the first letter of the alphabet. Once we get this score, it needs to be multiplied by (index + 1) because the name

indices start from 0. Score of the first name needs to be multiplied by 1, not 0.

Non-Abundant Sums

A perfect number is a number for which the sum of its proper divisors is exactly equal to the number. For example, the sum of the proper divisors of \(28\) would be \(1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14 = 28\), which means that \(28\) is a perfect number.

A number \(n\) is called deficient if the sum of its proper divisors is less than \(n\) and it is called abundant if this sum exceeds \(n\).

As \(12\) is the smallest abundant number, \(1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 6 = 16\), the smallest number that can be written as the sum of two abundant numbers is \(24\). By mathematical analysis, it can be shown that all integers greater than \(28123\) can be written as the sum of two abundant numbers. However, this upper limit cannot be reduced any further by analysis even though it is known that the greatest number that cannot be expressed as the sum of two abundant numbers is less than this limit.

Find the sum of all the positive integers which cannot be written as the sum of two abundant numbers.

Solution

We can obtain the divisors by reusing the code from Problem 21:

private def divisors(n: Int): Seq[Int] = 1 +: (2 to Math.sqrt(n).toInt).flatMap {

case i if n % i == 0 => if (i != n / i) List(i, n / i) else List(i)

case _ => List()

}

Now it is easy to check whether a number is abundant. Simply compare the sum of its divisors with the number itself:

private def isAbundant(n: Int): Boolean = divisors(n).sum > n

But how do we tell if a number is the sum of two abundant numbers? Checking all possibilities would be inefficient. In the worst case, we would need to check every pair of numbers, which leads to \(O(n^2))\) complexity. But there’s a way to make it linear!

If we subtract an abundant number \(a\) of ouf the number \(n\) we’re checking, then we only need to see whether

the different is also abundant. There is one problem, however, with our simple isAbundant method. It recomputes the

divisors every time, which is wasteful.

Once we know all the abundant numbers within a given range, we determine whether a number is abundant

(within that range) by simply checking if it’s inside the set of known abundant numbers.

The wording here is crucial, string Set rather than a List to do that search is crucial.

Here’s the complete solution:

object Euler023 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): Any = {

val limit = 28123

val abundantNumbers = (1 to limit).filter(isAbundant)

val abundantNumbersSet = abundantNumbers.toSet

(1 to limit).filterNot { n =>

isSumOfTwoAbundant(n, abundantNumbers, abundantNumbersSet)

}.sum

}

private def isSumOfTwoAbundant(

n: Int,

abundantNumbers: Seq[Int],

abundantNumbersSet: Set[Int]

): Boolean =

abundantNumbers.takeWhile(_ <= n).exists { a =>

abundantNumbersSet.contains(n - a)

}

private def isAbundant(n: Int): Boolean = divisors(n).sum > n

private def divisors(n: Int): Seq[Int] = 1 +: (2 to Math.sqrt(n).toInt).flatMap {

case i if n % i == 0 => if (i != n / i) List(i, n / i) else List(i)

case _ => List()

}

}

On my notebook it runs in less than a second.

Lexicographic Permutations

A permutation is an ordered arrangement of objects. For example, \(3124\) is one possible permutation of the digits \(1, 2, 3\) and \(4\). If all of the permutations are listed numerically or alphabetically, we call it lexicographic order. The lexicographic permutations of \(0\), \(1\) and \(2\) are:

\begin{align} 012, 021, 102, 120, 201, 210 \end{align}

What is the millionth lexicographic permutation of the digits \(0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8\) and \(9\)?

Solution

Scala’s standard library is so good that this problem can be solved in just a single line.

The .permutations create permutations, already in lexicographic order, so we just need to find the millionth one.

object Euler024 extends EulerApp {

override def execute(): String = "0123456789".permutations.drop(999_999).next()

}

It’s all Iterator-based, which means that there’s no need to store all the million permutations in the memory.

Perfectly readable and efficient. I wish all problems could be solved like that!

1000-digit Fibonacci Number

The Fibonacci sequence is defined by the recurrence relation:

\(F_n = F_{n - 1} + F_{n - 2}\), where \(F_1 = 1\) and \(F_2 = 1\)

Hence the first 12 terms will be:

\begin{align} F_1 &= 1\\ F_2 &= 1\\ F_3 &= 2\\ F_4 &= 3\\ F_5 &= 5\\ F_6 &= 8\\ F_7 &= 13\\ F_8 &= 21\\ F_9 &= 34\\ F_{10} &= 55\\ F_{11} &= 89\\ F_{12} &= 144 \end{align}

The \(12th\) term, \(F_12\), is the first term to contain three digits.

What is the index of the first term in the Fibonacci sequence to contain \(1000\) digits?

Solution

This problem doesn’t need any optimizations to be solved in milliseconds. It’s perfectly fine to store 1000-digit